Lorenzo Perilli: Generative Artificial Intelligence. How have we come so far?

Lorenzo Perilli, Director of the Department of Literature, Philosophy and Art History at the University of Rome Tor Vergata, is a philologist and historian of

What we can learn from the Facebook blackout

Marco Avidano*

On 4 October 2021, Menlo Park’s giant system that runs several platforms, Facebook, Instagram, Whatsapp and hundreds of other services suffered a worldwide blackout that lasted over 7 hours.

One of the effects that attracted the most attention was that the platform’s employees could not enter the company’s buildings because the badges with which access is regulated had also stopped working. According to the New York Times, Facebook sent a team of technicians to its data centres in California to fix the configurations manually.

The fact that manual intervention with physical access to the systems was necessary means that the problem occurred at a very low level on the network, although knowing the actual causes of what happened is difficult. The only thing that is certain is that this kind of problem can and does happen: people say it is impossible, but we know that if something can go wrong it will, and it is important to assess the possible consequences beforehand, especially in relation to the way our society is set up today and in the future.

There is a profound misperception of the network: nowadays we act taking connectivity for granted. We plan our lives by considering the network as always present, just as there is air to breathe, or water to drink. But this is not the case, as we see from events such as this one at Facebook.

Beyond the specifics of the Facebook blackout, what is worrying is that systems that manage more and more aspects of our daily life, let’s say offline, often do not have safety nets. We talk about alternatives that take into account the unavailability of the network: but having alternatives that have the sole purpose of redundancy is inconvenient, expensive, and affects profit. Keeping such alternatives up and running and training staff to use them is even more expensive, so that increasingly a second way is not considered at all. The result is that the blocking of one part of the system brings all activities to a standstill, even those that have little or nothing to do with the part actually affected by the malfunction.

All of Facebook’s systems are set up as a totally autonomous ecosystem, a network that depends only on itself: but such a system, however sophisticated and enormous, is exposed to incidents for which there is no backup. And this is what happened.

In order to solve the blockage, physical access to the machines was required, but physical access is always strictly regulated, for obvious security reasons. The necessary authorizations could not be obtained quickly because communications were complicated by the side effects of the blockage: badges, emails, internal systems could not be reached. At the same time, there were problems with the availability of technicians and the coordination of interventions, again due to the blockage of communication tools.

While the blockade was in progress, I tried to analyze the situation as far as I could remotely, because, as a system administrator, I have a strong interest about these episodes, especially if they happen to giants like Facebook, to understand what had happened and learn from the mistakes to avoid repeating them.

The DNS

From a first and basic analysis, it could be seen that Facebook’s domain was untraceable because the DNS were unreachable. The DNS, Domain Name System, were failing not because it was directly blocked, but because the servers on which it ran were unavailable in the network. The entire Facebook network was unreachable.

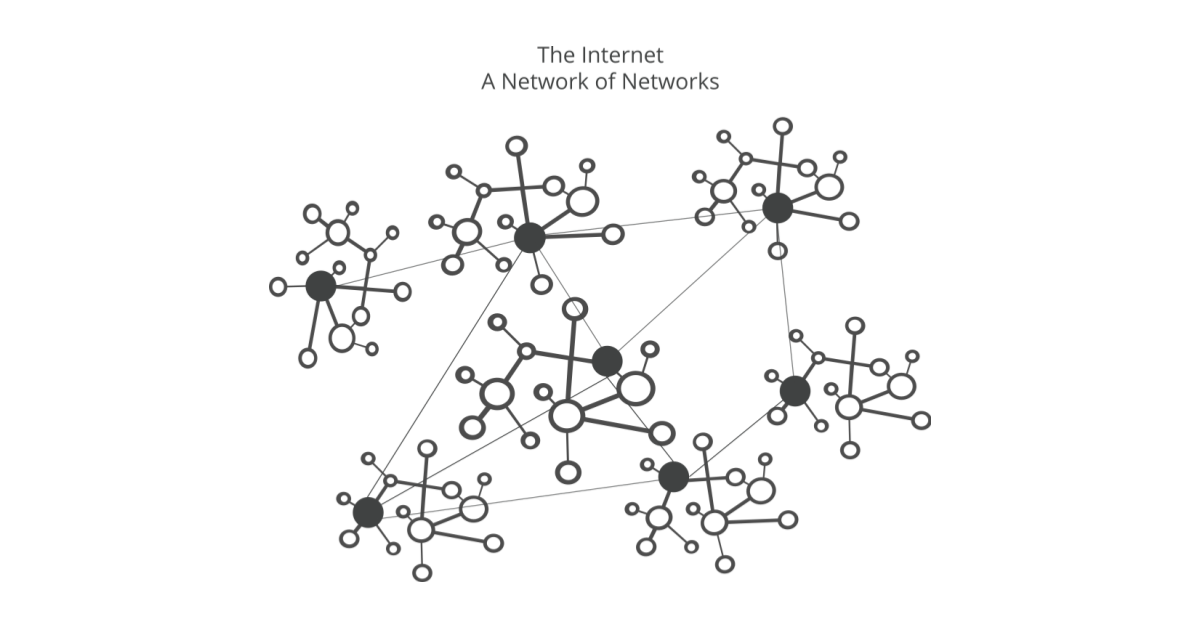

To fully understand this event you need to have a low-level knowledge of how the Internet works, but you can make comparisons with the analogue world to understand what happened.

The DNS is like a phone book: if you know the name of the person, you go to the phone book and find the address and phone number. The Facebook address book itself was fine, it was where they left it the last time, they used it. But it was as if they had forgotten where it was: the information was all there, but who knows where. Or to be more precise: they had forgotten where the city was with the house in which the address book was contained, as if it were a new Atlantis. A city in which all the other people recorded in the address book were also located. In fact, even if they had a copy of the address book with them, it was not possible to contact the other people, as they were in a city that was no longer known. In this example, the city was Facebook, with all its services.

Returning to the reality of what happened, all the network protocols that regulate the ways in which the various components of the Internet can find each other come into play at this point.

The error had occurred in one of these protocols, a very low level of the network, through which the various systems communicate their existence in relation to other systems: I know you, you know another person, so through you I can get in touch with this third party. If you disappear, I know that this other person exists, but I cannot reach him or her because you were the intermediary. The BGP protocol maintains these relationships between the main nodes of the network: what happened was that Facebook had stopped telling the rest of the world that it existed, and how to reach it, because of an error in the configurations at the BGP level.

When the error was fixed, it then took a few hours before the system was fully restored worldwide: these protocols are quite slow, and information takes time to propagate throughout the network, in a kind of word-of-mouth.

The economic damage

The media spoke of enormous economic damage, estimated at billions of dollars. However, this was a fictitious and temporary loss, caused by the immediate drop in the value of Facebook’s shares. This is the stock market, where billions of dollars disappear or are created as if out of thin air, and it is hardly indicative of what actually happens in the real world, although the effects of such often senseless fluctuations have even tragic effects on people’s lives.

The real and direct losses caused by this downturn are the lost earnings from advertising. Services that only use Facebook to log in to their accounts were also directly affected: e-commerce sites and services whose activities have nothing to do with Facebook, except for the login, found themselves blocked for hours because users could not access their accounts.

Centralisation and gigantism

The problems here are the gigantism of these networks and their centralisation.

The Internet was born out of the evolution of military networks, the key point of which was decentralisation: this was what guaranteed its operation in all circumstances, even in the event of nuclear attacks that could have blocked part of it. There were to be no indispensable key nodes, the so-called Single Points of Failure: points that, if blocked, would lead to the complete collapse of the system.

This is how the Internet was born, and how it has evolved, always keeping this point in its evolution: today it is a global network with billions of interconnected nodes, and this is what guarantees its robustness. Sure, parts of the Internet may become unreachable: but the Internet itself is always there. Everywhere, and nowhere.

However, there is a tendency to forget these basic rules, and there is now a rush to centralization as if it were an Earthly Paradise where everything is nice and perfect: the Cloud.

A few days ago, another event happened, which made less news: one of the largest providers in the world, a company that manages about thirty data centers internationally, experienced a problem similar to that of Facebook, disappearing from the Internet for about an hour, due to an update of some network equipment that went very wrong. As a result, tens of thousands of sites and services were unreachable for more than an hour: not only normal sites, but also services such as billing systems, medical bookings, and, of course, Smart Home management systems that rely on online servers.

The immoderate growth of these networks entails a huge effort to manage them. With tens or even hundreds of thousands of them, it is unthinkable that these machines should be managed individually, carefully: they are then grouped into sections, and updates and new configurations are sent out in bulk. However, it can happen that these new configurations are wrong, or that the network sections to which they are to be sent are selected by mistake: the consequences can be tragic, up to complete blockage and the need for a manual reboot, as seems to have happened to Facebook.

Today, it seems that we are always late. Even before starting a new job, we are already behind schedule. Work is planned and half the time allocated. This race for uncontrolled growth, as if time were running out, is creating the conditions for the perfect storm.

An overexposed network

The problem is further exacerbated by the fact that the Internet is now being used to manage devices that were not born with the online in mind: take for example centralised heating, air conditioning, TV, refrigeration systems, and so on. But also industrial lines: nowadays practically everything is connected to the Internet and can be managed remotely.

It’s certainly a great convenience: we saw this especially during the lockdown period, during which activities were able to go on despite the difficulties in moving around.

But things have to be done carefully: this convenience must not become the only way, otherwise the network itself becomes one of those Single Points of Failure which, if they fail, lead to a complete shutdown. Of course it is convenient to be able to turn on the heating at home with my smartphone on my way home from work, but it is not good to be able to do it only with your smartphone: it is absurd to remain in the dark at home just because a server on the other side of the world is unreachable. The risk is that we lose control of our lives.

It should also be borne in mind that every time a new door is opened, a passageway is created that can be abused by malicious persons. The fact that it is a secondary access does not mean that passing through it has less power: a burglar entering the house will do the same damage whether he enters through the main entrance or through the cellar window. And secondary entrances are the most attractive to burglars because they are always less controlled.

Malicious attacks

In addition to human error, network failures can also occur intentionally. Cyber-attacks are the order of the day: often these are actions aimed at financial gain, as in the case of ransomware with demands for ransom payments to recover data.

But this is not the end of the story: these actions can also be carried out by malicious governments, either to control the population of their own country, or against other countries. It has been said many times that World War III will probably be fought online: unfortunately this is not science fiction. In such a scenario, the cards in the game are completely shuffled: the most vulnerable countries become the most technologically advanced ones, since the population is increasingly and exclusively dependent on the net for every daily activity. And you don’t need large armies or brave and courageous soldiers to be the strongest: mathematicians will make the difference.

Events such as the Facebook incident are important, if not fundamental, for all of us: they give us the opportunity to objectively assess our dependence on the net. All too often we have no idea how true this is: we can no longer read a road map, we can no longer look up information in an encyclopaedia (if we have one), and at best we can remember our phone number by heart. We should all reflect on these aspects, and those who manage these large systems should feel a little less powerful, less infallible and secure, and aware of the responsibilities they are taking on. We should realise that the Net may not be as reliable as people think. Because it isn’t.

*computer security expert, he is a network administrator.

Lorenzo Perilli, Director of the Department of Literature, Philosophy and Art History at the University of Rome Tor Vergata, is a philologist and historian of

The Italian initiative, promoted by the Ministry of Education and Merit, as part of the Robotics Championships project, aims to enhance students’ scientific and technical

Sold out for the first training day “Dicolab. Cultura al digitale” in Genoa. The 25 places available for the first two courses in Genoa sold

Io Do Una Mano ( I Give a Hand) is a non-profit organization with the goal of helping people – especially children – with congenital

Write here your email address. We will send you the latest news about Scuola di Robotica without exaggerating! Promised! You can delete your subscription whenever you want clicking on link in the email.

© Scuola di Robotica | All Rights Reserved | Powered by Scuola di Robotica | info@scuoladirobotica.it | +39.348.0961616 +39.010.8176146 | Scuola di robotica® is a registered trademark