MEET Digital Culture Center and Scuola di Robotica combine their expertise and visions to create a training initiative: the Immersive Education Program. This program enhances

The Lifelong Kindergarten (MIT Media Lab) research group, led by Mitchel Resnick, was the creator of the Scratch programming language and its online community. Scratch was born to help children develop their creative thinking.

In fact, this group developed and adopted an educational approach – using technologies, activities and strategies – to engage students with creativity-based education. The research group is inspired by the learning and didactics adopted in kindergartens, where children develop their creative thinking, going through all phases of the realisation of a project: they develop an idea, create a project based on it, experiment with alternatives, collaborating and sharing experiences with their friends.

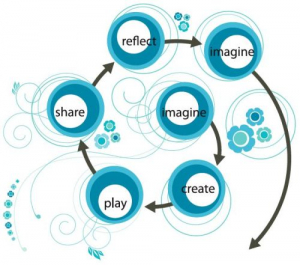

In the book “Lifelong Kindergarten – Cultivating Creativity through Projects, Passion, Peers, and Play” Resnik takes as an example a group of children playing with building blocks: someone starts to build, at the same time someone else imagines a story that matches the construction. But when the structure collapses, the children try to make it more stable by modifying it, and then readjust the story, or invent a new one. So, this process of imagination and play is repeated, over and over again, interspersed with phases of reflection on what has been done (why did the construction collapse? How can we make it better?) and sharing ideas among groups. The author imagines this process as “the spiral of creative learning” that is repeated endlessly.

Picture author Wesley Fryer

Creative Commons 2.0 Generic attribution

The idea of the research group is to extend this process at every stage of education, so much so that Mitchel Resnick – in the text quoted above – writes:

“My nomination for the greatest invention of the previous thousand years (2nd millennium, ed)? Kindergarten.”

nd shortly afterwards

“[…] I believe the rest of school (indeed, the rest of life) should become more like kindergarten”.

What do we mean when we talk about “creative thinking”? This is a name that Resnick uses as an alternative to “creativity“, whose definition, according to Online Treccani Dictionary (ITA) is:

“Creative virtue, ability to create using intellect and imagination. In the field of psychology, the term has been taken to indicate a process of intellectual dynamics that has as its characterizing factors: particular sensitivity to problems, ability to produce ideas, originality in conceiving, ability to synthesize and analyze, ability to define and structure their experiences and knowledge in a new way.”.

We are, therefore talking about an intellectual capacity that allows us to conceive and solve problems, using imagination and critical analysis. Consequently, we do not mean “creativity” only what is transformed into artistic expression (a painting, a sculpture, a poem, a work, …), but creativity is also used by scientists who develop new theories, technicians who imagine new products, students who find brilliant ways to solve problems, and so on. It is evident, if we consider creativity from this point of view, that this is a necessary capacity in our schools, and especially in our lives.

Mitchel Resnick in “Lifelong Kindergarten” goes further in the analysis of creativity. He writes that there are two types of creativity, one with an uppercase “C” and one with a lowercase “c”. The first one is the propriety of great scientists, artists, great managers: in short, that of those who create totally new and innovative ideas and inventions. The second one is the kind of creativity that leads us, in our daily lives, to find brilliant or useful solutions to our problems. Even if, perhaps, such ideas are nothing new for the world, they are new for us. The example given by the author is the paper clip: the invention of the paper clip was creativity with a capital “C”, every intelligent way to use a paper clip in everyday life is creativity with a small “c”.

Even if I do not share the vocabulary (“c” capital or lower case) it is clear that the two types of creativity exist and are different. The one called with a lowercase “c” should not be overlooked. On the contrary, we must ensure that our students develop it and adopt it in their lives.

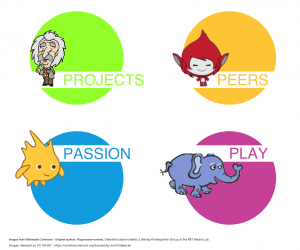

Lifelong Kindergarten group converts these ideas into a methodology, a didactic approach, called the 4P’s process of creative learning. This approach is based on 4 words, each of which begins with the letter “P”: Project, Peers, Passion, Play. Each word is associated with a meaning, a role in the educational method.

The hereunder ideas derive from education to creativity, and use in coding and programming, but can be used in several educational areas, and are particularly suited to teaching by robots. Moreover, these methods are also interesting to realize lessons without the help of robotics.

Let’s go now to analyze the 4P’s.

In the classic approach to teaching, we usually talk about problems, questions, exercises. It is difficult, however, to think about working on projects. If instead of a problem or abstract case, you work on a project, learning is better, more skills and abilities are developed in a more motivating context. Problems and exercises become an integral part of the project, take on a concrete meaning, and are interrelated. In this way the work is made more concrete, you are able to engage your students more. Furthermore, students learn to deal with problems not in a superficial way or as an end in themselves, but rather by applying them to the real world, and they are able to understand how to apply the same approaches to future problems.

In the classic approach to teaching, we usually talk about problems, questions, exercises. It is difficult, however, to think about working on projects. If instead of a problem or abstract case, you work on a project, learning is better, more skills and abilities are developed in a more motivating context. Problems and exercises become an integral part of the project, take on a concrete meaning, and are interrelated. In this way the work is made more concrete, you are able to engage your students more. Furthermore, students learn to deal with problems not in a superficial way or as an end in themselves, but rather by applying them to the real world, and they are able to understand how to apply the same approaches to future problems.

What do peers mean? We can imagine: “colleagues, fellow, similar” and some other related sense. In Resnick’s idea, this concept is related to the fact that most creative learning – and I would like to add not only that – is not individual but is a social activity. Learning is effective when there is communication, when people exchange ideas and collaborate, confront each other and share both doubts and solutions.

When we work on projects that fascinate us, that we love, we are willing to work longer and harder. If we are passionate about what we do we tend to persist in case of difficulties, not to give up and try to give the best of ourselves. This tends to mean that we work better, with more commitment and effectiveness, when we are passionate about something than when we have to do something we are not passionate about.

When we work on projects that fascinate us, that we love, we are willing to work longer and harder. If we are passionate about what we do we tend to persist in case of difficulties, not to give up and try to give the best of ourselves. This tends to mean that we work better, with more commitment and effectiveness, when we are passionate about something than when we have to do something we are not passionate about.

The word play, on the other hand, contains several meanings: playing (a game), having fun, but also playing an instrument, taking part in something, participating, acting. For these reasons it is a word really full of value: all these activities have a deep didactic sense. In all these moments, we continuously experiment, try new things and situations, we take risks and expand our boundaries also leaving our comfort zone. Doing this, we are learning. Further, if we think only of the concept of play, understood as having fun, we can realize that learning is better and more effective if done through activities that make us have fun: they allow us to increase engagement and interest.

Let us return, instead, to the first P of these principles: projects. In fact, there is another effective teaching methodology that I believe is the natural evolution of the 4Ps: Project Based Learning (PBL).

The method requires that the students’ learning takes place in a mainly experiential way while working in groups on projects. The basic element of the method is that the project is as real and concrete as possible, that it responds to a truea and tangible problem, of which we want to try to identify a solution, similar to the way researchers and scientists work.

In project work, students ask questions and reflect, propose hypotheses and explanations, discuss their ideas. It is a model for classroom activities that move away from ordinary short, isolated, teacher-centred lessons. It is also a useful approach for students to establish a connection with life outside the classroom, analysing problems and developing skills related to life in the real world. In this way, they can develop the ability to work in groups but, above all, active learning and critical thinking.

As far as face-to-face lessons are concerned, these must not disappear. However, they should no longer be at the heart of the teaching activity, but rather play the role of moments in which knowledge can be discussed and consolidated. Furthermore, they must function as useful moments for support, for the evolution of the project. Moreover, the duration of the activity itself also changes: the work on a project tends to last long, even more than an ordinary lesson.

As a result, the role of the teacher also changes. He or she will no longer be the central element of the lessons, the knowledge giver, but will have to assume more of the role of guide or coach, accompanying students in their learning – which must be more active and participated -, supporting them and providing them with suggestions, advice, evaluations and feedback.

Exercises and problems, which in traditional didactics are assigned or solved in class, as seen emerges naturally during the project analysis flow. Again, as seen a project also tends to be long and potentially complex. Thus, the analysis of the individual problem usually leads to further problems that needs to be solved. At this juncture, we do not neglect that, often, it is also useful to proceed by trial and error. This is how critical thinking, the ability to confront, to document and to share, develops.

As far as documentation and the study and sharing phase are concerned, moreover, project-based learning lends itself particularly well to the realisation of real didactic experiences. It is extremely interesting, if possible, to involve people from outside the school environment: on the one hand, it is interesting to bring students together with experts in the field whose problem is being analysed. As far as sharing is concerned, on the other hand, it is always interesting to disseminate – with other classes, on the school’s website, on a blog, on a social page… – the obtained results.

Another fundamental element of project-based learning is the critical assessment, i.e. a series of moments in which teachers, or other experts, provide comments and evaluations on students’ work. In this way, students understand the quality of their work and the adopted strategies, understand and address any gaps or errors and may eventually recalibrate their approach and strategy. As for errors: let’s not stigmatise them, they are a fundamental element of learning.

These stages of documentation, study and sharing – however they are carried out – are fundamental to learning. In fact, paraphrasing the philosopher and pedagogist John Dewey

“We do not learn from experiences, but from reflecting on them”.

Within the ROBOESL project, dedicated to failure and early school leaving, we have developed a series of Learning Scenarios inspired by PBL and applied to robot education. You can find them on the dedicated page on the project website. This methodology was chosen to provide students with concrete and motivating contexts on which to work.Also within the project We Are The Makers – IoT in Education scenarios based on the project work have been developed, you can find them from the dedicated page. Try to apply some of these scenarios in your classrooms, adapt them to your and your students’ needs. We invite you, then, to try to identify problems that your classes can work on, and remember: make sure that they are passionate about what they are working on, that they can experiment and have fun and that dialogue and discussion are always facilitated.

Adam F. C. Fletcher, The Excitement of Project Based Learning

adamfletcher.net/the-excitement-of-project-based-learning/

Joseph S. Krajcik e Phyllis C. Blumenfeld, Project-Based Learning In: The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences, Cambridge University Press, 2006, R. Keith Sawyer (ed)

Lifelong Kindergarten group, Learning Creative Learning (online course and community)

https://learn.media.mit.edu/lcl/

Rene Alimis et al, ROBOESL Output 2: curriculum for blended (online and face to face) training course for teachers, p 10-13, 2017

http://roboesl.eu/?page_id=595

Seymour Papert, Mindstorms: Children, Computers and Poweful Ideas, Basic Books, 1980

Digital edition courtesy of Papert’s family and thanks to MIT Media Lab hosting available here https://mindstorms.media.mit.edu/

Mitchel Resnick, Give P’s a Chance: Projects, Peers, Passion, Play, MIT Media Lab, 2014

https://web.media.mit.edu/~mres/papers/constructionism-2014.pdf

Mitchel Resnick, Projects, passion, peers and play, The LEGO Foundation, CREATIVITY MATTERS NO. 1, p. 14-17

https://www.legofoundation.com/media/1664/creating-creators_full-report.pdf

Mitchel Resnick, On Seymour Papert, The Brainwaves Video Anthology, produced by Bob Greenberg, 2017

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZoczAscGYeQ

Mitchel Resnick, Come I bambini – Immagina, crea, gioca e condividi, Erickson, 2018

Original edition: Lifelong kinderarten, Cultivating Creativity trough Projects, Passion, Peers and Play, The MIT Press, 2017

MEET Digital Culture Center and Scuola di Robotica combine their expertise and visions to create a training initiative: the Immersive Education Program. This program enhances

For the achievement of the Horizon Europe project results, PRAESIIDIUM, numerous research groups are combining their expertise to develop innovative strategies for the prevention of

STEP FuturAbility District is a dynamic, interactive experiential journey that allows students to immerse themselves in today’s ongoing digital revolution. For schools, we offer the

The autumn program in the regional Hubs of the Dicolab. Digital Culture project is packed with opportunities for those who want to learn about the