Lorenzo Perilli: Generative Artificial Intelligence. How have we come so far?

Lorenzo Perilli, Director of the Department of Literature, Philosophy and Art History at the University of Rome Tor Vergata, is a philologist and historian of

Girls not interested in technology?

The STEM course at the Einaudi Casaregis Institute in Genoa

Are girls not interested in technology?

This question, in its various forms, is the starting point for hundreds of articles, projects, sociological surveys, and statistical research.

The numbers are not favorable.

In Italy, apart from a few successful women who have attained high positions in digital technology fields, there remains, and perhaps has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, a heavy under-representation of women in techno science professions, careers, and studies.

The picture does not change, or only slightly, in Europe.

If not for reasons of distributive justice, strictly economic reasons call for a drastic change of course.

The Gender Equality Index 2019 states that the large under-representation of women in sectors such as ICT corresponds to a great waste of highly qualified human resources and economic potential (EIGE, 2018d). Reducing gender segregation in the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) sectors would increase GDP in the EU by around €820 billion and create up to 1.2 million more jobs by 2050 (EIGE, 2017a).

The Gender Equality Report 2020, which has just been released, is even more focused on our issues: Digitalisation and the future of work, and Gendered patterns in the use of new technologies.

Despite the overall growth and high demand for related skills in the labor market, only 20% of graduates in related fields are women and the share of women in ICT jobs is 18% (a decrease of 4 percentage points since 2010!). According to the 2020 Index, there is also a significant gender gap between researchers and engineers in high-tech sectors who could be mobilized in the design and development of new digital technologies – the untapped potential of talented female researchers.

Girls choose non-technological professions

Technological professions have been created by males, and cut and sewn to their needs, their life rhythms, their relationships within the family.

Women all over the world who bear the burden of caring for children, the elderly, and disabled relatives are often unable to maintain the same working patterns as men.

From this point of view, the European Institute for Gender Equality, which is responsible for the above-mentioned Index, has put forward a number of proposals:

– since women run a slightly higher risk than men of being replaced in their jobs (e.g. in office work) by digital machines; and the newly emerging jobs are often concentrated in the male-dominated ICT and STEM sectors, it would be possible to promote equality by, for example, upgrading the skills of certain jobs mostly held by women;

– Eliminating stereotypes and gender bias from the assessment of job performance and especially eliminating them from jobs in the platform economy;

– Ensuring social protection for self-employed women in the platform economy. About half of the self-employed mothers are not entitled to maternity benefits in the EU and access to parental leave is limited in some Member States. The lack of social protection became particularly problematic during the COVID19 crisis, which highlighted the importance of access to, for example, unemployment and sickness benefits.

According to the Index, the increased platform economy due to COVID is unlikely to lead to an improvement in social protection measures for women, which requires specific measures to support work-life balance, the latter being borne mainly by women.

The STEM course for female students at the Einaudi and Casaregis Institutes in Genoa

Since 2008, when we became the National Centre of the Roberta project, girls discover robots, Scuola di Robotica has been involved in what is called in the world Gender Education, the development of appropriate methodologies to promote STEM among girls and young women.

Recently, at the end of January 2021, Scuola di Robotica concluded, in collaboration with the Headmistress, Professor Rosella Monteforte, and several Teachers of the Galilei-Einaudi-Casaregis Institute, a course dedicated to female students and financed by the Ministry for Equal Opportunities call for proposals dedicated to gender education, won by this Institute.

About 50 students from the Einaudi and Casaregis institutes – third and fourth classes – took part in the course. The Einaudi Institute has a technical-economic course, attended mainly by female students, and the Casaregis Institute has a commercial and marketing services course.

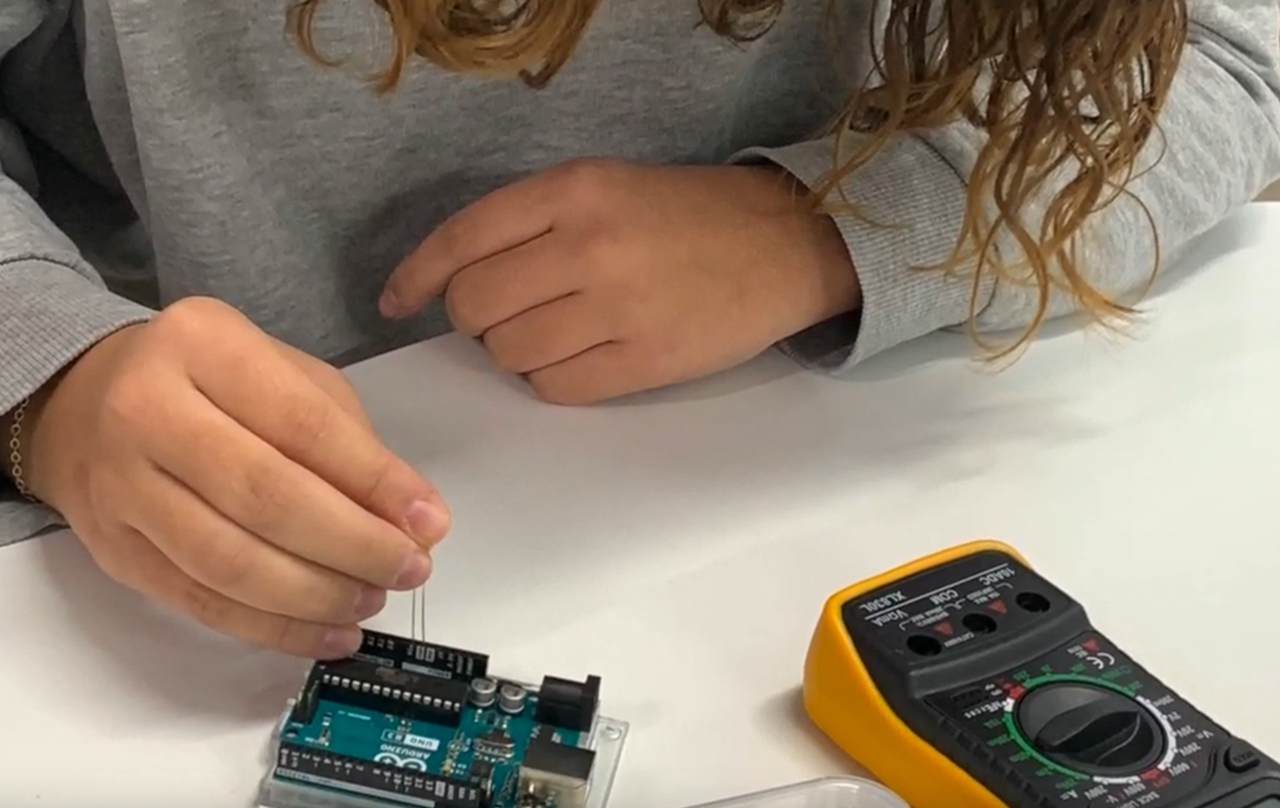

The course program included an introduction to coding and educational robotics, using the Byor kit.

Using the kit and the Tinkercad simulator simultaneously, the course provided an approach to the world of electronics and the many uses of Arduino.

The framing of the Makers’ movement and the freedom and variety of design and creation that distinguishes them provided a springboard to help break down the wall of cultural resistance that keeps girls away from technology.

Starting from the creation of a simple electrical circuit, the course touched on the implementation of photoresistance, ultrasonic sensors, DC actuators, LEDs, and piezoelectric components.

The students were divided into groups of about 8 participants per group, none of them had any experience in coding and robotics, and most of the course hours were spent in distance learning, which is not an easy activity for a laboratory course on programming a small robotics kit.

The difficulties of lessons with students at home emerged: the lack of adequate equipment at home (many students don’t have a PC at home or can’t use it for their lessons), the Internet, space. These problems were compounded by the difficulty of programming BYOR from a mobile phone, which is now the only technological tool available to the world’s population of students.

Despite these not insignificant difficulties, the course was successful, and all the students got involved, with varying degrees of interest and commitment.

After initial reactions of hostility, disinterest, detachment and fear of making mistakes, they all carried on with their programming tasks. The fact that they worked in a smaller group than the class group helped the collaboration between the participants.

Some of them were very curious, some wary, but most applied themselves and gradually became more and more intrigued: gaps then used the kit freely, adding creativity and artistic ideas.

The end of the course took the form of a 4-hour hackathon in which all the girls who took part in the meetings connected simultaneously to hear rules and suggestions regarding the last challenge. The groups, slightly readjusted (5 girls per group), worked on their own ideas both from the design and the implementation point of view, presenting in plenary the result obtained during the afternoon through slides, images, and demonstrations of the functioning of the prototypes.

The problems linked to the female stereotype in the face of technology emerged during the lessons: “My brother assembled the kit”. But at the end of the day, they all expressed their happiness – and pride – at having completed a task they had never imagined they could begin.

Conclusions

With our course, we certainly do not think we have solved the problem of women’s underrepresentation in technology subjects and professions. In many respects, it is a matter of policy decisions by states to address the problems of the time and manner of women workers.

At the same time, a continuous information campaign will be needed among families, who are not informed about the skills required by the labor market today, e-skills, and robotics. Families often pander to the female stereotype by directing their daughters towards curricula for professions that unfortunately will not have a real working future.

If several thousand courses like the one held at Einaudi Casaregis in Genoa could be held in Italy, we would certainly see an important change in the cultural paradigm on this issue.

Lorenzo Perilli, Director of the Department of Literature, Philosophy and Art History at the University of Rome Tor Vergata, is a philologist and historian of

The Italian initiative, promoted by the Ministry of Education and Merit, as part of the Robotics Championships project, aims to enhance students’ scientific and technical

Sold out for the first training day “Dicolab. Cultura al digitale” in Genoa. The 25 places available for the first two courses in Genoa sold

Io Do Una Mano ( I Give a Hand) is a non-profit organization with the goal of helping people – especially children – with congenital

Write here your email address. We will send you the latest news about Scuola di Robotica without exaggerating! Promised! You can delete your subscription whenever you want clicking on link in the email.

© Scuola di Robotica | All Rights Reserved | Powered by Scuola di Robotica | info@scuoladirobotica.it | +39.348.0961616 +39.010.8176146 | Scuola di robotica® is a registered trademark